Outwitted

I might have outwitted myself. My post entitled Vanna Depresses was a tongue-in-cheek look at the division between self-publishing and traditional publishing. But if you've never heard of a "vanity press" or a "hybrid publisher," then that post will probably seem a little obscure. So here's a quick primer...

"Vanity press" is a term used within the publishing industry for companies that accept money from authors to publish their work. The theory is that if someone is willing to pay for publishing, then they are probably doing it for reasons of vanity -- that is, they just want to see their work in print.

First, I don't think this is a fair assessment. Authors write -- and publish -- for many reasons. In fact, many of those who are accused of "vanity publishing" couldn't care less how many books they sell, how many awards they win, or how many positive reviews they receive. Everyone who writes has something to say, and choosing not to wait for permission should not be confused with vanity.

Second, there is a wide range of services available to self-published authors. Sure, many people are only looking to make a buck ... but there are also many reputable service providers who do a great job of improving an author's work in exchange for fair payment. And there are "hybrid publishers" who publish works on behalf of authors while sharing the costs of production and promotion.

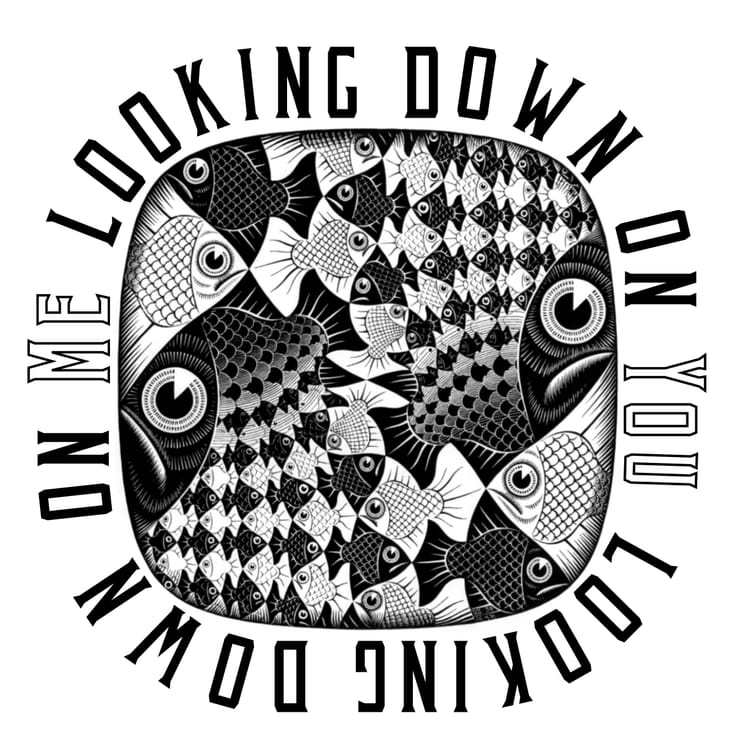

Working as an author, a service provider, and now as a hybrid publisher, I take exception to black and white statements that lump writers into two camps: those who pay to produce and promote their own work -- the "self-published"; and those who get paid to write -- the "published." As much as some people would like to establish clear lines between traditionally published works of merit and self-published works of vanity, there are many shades of grey on the publishing spectrum.

It has never been easier to produce a book, which has led to an understandable concern by serious writers that their industry -- and literature as a whole -- is being watered down. Even as a self-published author, I recognize that the tools which help me are also working against me. I see that the relative ease of publishing leads to such a glut of content that it is hard to stand out against the crowd.

I see every challenge as an opportunity, and I believe that quality will always be valued. It is all too easy to get caught up in the slog of self-promotion, to get lost in a sea of mediocrity. But those who focus on quality -- quality of content, design, production ... and relationships -- will find ways to break away from the pack.

I have nothing against traditional publishing, and most of the publishers I have met are delightful people. There is a good chance that I too will publish others' works "traditionally" at some point, and I might even shop my own stories to others. My beef is not with those who work in the traditional way -- where the publisher pays the author and takes on the risk associated with printing and distributing a book; it is with those who see that as the

onlyway -- and look down their noses at anyone who pursues a more independent path.

I chose to self-publish for many reasons, but my main reason was to learn. I felt that by managing the whole process -- from hiring an editor to producing the book to promoting it far and wide -- I would learn more, and in less time, than I would trying to land a traditional publishing contract. It has been a difficult journey, one that has actually grown my appreciation for publishers. But it has also been an eye-opener about the discrimination that exists within the literary community.

It is easy to see how there came to be an "us" and a "them" ... and it's

noteasy to bridge that gap. There are many practical reasons for those who promote works of literature -- bookstores, distributors, festivals, publications and more -- to work only with traditionally published authors. Dealing with established publishers provides some level of quality assurance, and consolidates both administration and communication. Having run a business for many years, I understand how difficult it is to deal with small, unknown "accounts." Nevertheless, the tendency to exclude self-published work from consideration is a form of discrimination, and in many cases it is -- to some degree -- a matter of vanity.

I hope that clears up a few things. So far, the most important lesson I've learned about publishing is that it's important to push aside vanity, work with great people, and emphasize quality in everything we do. No matter how we choose to publish a book, I believe that focusing on the right things will eventually lead to success.

Member discussion